***This post is part of The 3rd Wonderful Ingrid Bergman Blogathon, hosted by Virginie Pronovost of The Wonderful World of Cinema. ***

***Some spoilers***

“[Hedda] can be witty and charming. She’s knowledgeable and smart – and that is the problem. Hedda Gabler is too smart for her own good.” (Silver Screenings, par. 3)

I’ve been a classic film fan for a long time now and although I’m familiar with a lot of classic film stars, it took me a while to warm up to a few of them, one of which was Ingrid Bergman. I’m not sure why I didn’t adore her from the first, as I do now. Maybe it was her rather deep, throaty voice or her cool, dignified manner with a personable charm that has a way of sneaking up on you. I suspect part of the reason was because the first Berman films I saw was the iconic Casablanca (1942) where she plays a more angelic and somewhat perfect sugar-watery character (I read that even Bergman wasn’t too crazy about her character Ilsa Lund).

But as I got to see more of Bergman’s work, I realized my initial assessment about her was way off. Bergman’s performances have versatility and class and even in earlier roles like Notorious (1946) and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1942), her characters run the gamut of high and low class, beauty and beast.

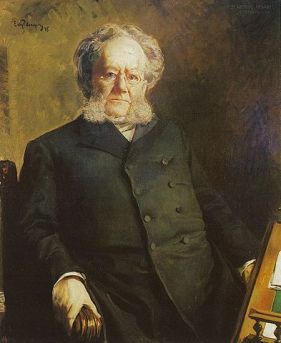

Photo Credit: Portrait of Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, who wrote Hedda Gabler in 1891, Ellif Peterssen, 1895, painting, private collection, from Nasjonalgalleriet; book Norske forfatterportretter, 1993: Orland/ Wikimedia Commons/PD Old

One of these more varied characters came later in her life in a TV film based on Henrik Ibsen’s glorious play, Hedda Gabler (1962). One of Ibsen’s strengths was his sympathy for 19th women and their limited role in Victorian middle-class society (as in the classic play, A Doll’s House). In many ways, the title character of this play is more complex and stronger than Nora Helmer. I believe only an actress with the versatility and dignity of Bergman could have played her so well.

I talk about the idea of the separate spheres in Victorian society in this blog post about another heroine that goes outside the boundaries of Victorian roles for women. Like Catherine Sloper in The Heiress, Hedda was raised without a mother but, unlike Catherine, she was adored by her father. Indeed, as MicFizzy states in the article “Pistols, Manuscript, and Vine Leaves in the Hair – Symbols in Hedda Gabler”, “[r]aised by her military father, Hedda possesses the characteristics of a soldier: pride of herself, but cold and imperious towards lower rank” (MicFizzy, par. 2). Not only that, “she grows up shooting and riding horses, instead of playing dolls like other girls…” (MicFizzy, par. 2). In other words, Hedda’s father raised her with all the privileges to a boy in the 19th century. This translated to a psychological reality of freedom, social respect based on merit, and intelligence.

Herein lies the key to Hedda’s character. On the one hand, Hedda has a taste for liberty, beauty and strength, qualities mainly accessible to men at the time. On the other, her future is dependant on how well she fulfills the Victorian prescription for women so “when reaches the age of 29… she needs a home to settle down in order to maintain her status and reputation” (MicFizzy, par. 3). She doesn’t just want to marry but craves acceptance into intellectual society, represented by her recent marriage to “a brilliant scholar but a dunce of a spouse…” (Silver Screenings, par. 9), played by Michael Redgrave. She wants to be a successful woman within the separate spheres, giving parties and showing off her husband’s accomplishments. Thus, as the Silver Screenings blog points out in the post “Ingrid Bergman as the Ignoble Hedda Gabler”, “[s]he… chafes at convention yet doesn’t have the guts to live an unconventional life” (par. 6). Being a woman, “she lives adrift in a society with pre-set roles for women…” (Silver Screenings, par. 12) and she is clearly unhappy in those roles. She wants it all – freedom and social acceptance, excitement and security. But because she wants it all in an era where wanting it all was impossible for most women, she fails at each role she attempts or, more to the point, she sabotages her possibility for success.

Her downward spiral is really the crux of the play. One of the fascinating things about watching Bergman in this play is how she understands to what extremes these psychological barriers and conflicts could bring an intelligent and ambitious woman, even to the edge of reason. Throughout the play, Bergman’s Hedda “laughs at the thought of a monotonous life, then starts to cry and nearly becomes hysterical” (Silver Screenings, par. 13). Bergman understands Hedda’s impossible predicament:

“[A]fter the wedding, Hedda realizes her self-worth can not be realized; her control is limited to the house. She will have no value outside the house due to the fact it is unthinkable for women to receive acceptance from public and professional fields.” (MicFizzy, par. 3)

Unfortunately, here, Ibsen falls into the conventional line of thought of his time – if a woman is deprived or rejects her “true calling” (i.e., being a happy housewife and mother), she directs her energies towards creating drama and wrecking the lives of those around her. But the lives Hedda destroys, including her own, do not stem from a defect of character but from the battle between how what society expects of her and what she was raised to expect of herself.

Photo Credit: Illustration of Henrik Ibsen’s play Hedda Gabler as staged at Kristiania Theater. I’m not sure what scene this is but I’m guessing one of the scenes of Hedda and Judge Brack, maybe even the scene before the tragic ending. Illustrated by Christian Krohg and appeared 14 March 1891 in Skilling-Magazin: Ordensherre/ Wikimedia Commons/PD Old

This is why the ending of the play is more than just desserts. We might expect Hedda, after having caused so much grief to those around her, to end her life because the guilty must be punished according to Victorian morality. Preceding the suicide is a rather seedy confrontation between Hedda and a family friend, Judge Brack (Ralph Richardson) where blackmail and a demand of sexual favors are involved. Hedda kills herself with the dignity and courage she has carried on throughout the play. So,

“[h]er suicide is not a cowardly action; rather it is a part of her rebelling against the society. Born free, Hedda cannot stand the fact she will be in Brack’s control to avoid scandal. Her carefully designed death proves to the readers that she is in control of nobody but herself.” (MicFizzy, par. 6)

So Hedda maintains control over her life until the end, even in death.

Bergman’s Hedda in black-and-white may be quite a bit older than the 29-year-old Hedda in the play (she was, in fact 47) but her complexity and dignity is ageless. I don’t think many actresses could have portrayed Hedda as the feminist heroine she’s become over the years. Indeed, “Hedda Gabler… [reveals] the true cruel and dark side of the male-dominated society” (MicFizzy, par. 1).

Works Cited

MicFizzy. “Pistols, Manuscript, and Vine Leaves in the Hair – Symbols in Hedda Gabler.” Douban.com. douban.com, 2005-2017. 19 June 2009. Web. 23 August 2017.

Silver Screenings. “Ingrid Bergman as the Ignoble Hedda Gabler.” Web blog post. Silver Screenings. WordPress. 26 August 2016. Web. 23 August 2017.

Very interesting review! Hedda Gabler is not one of Ingrid’s most well-known films, but it is a good one. I also saw Ingrid Bergman first in Casablanca and I agree it’s not her most exciting performance (but I love her of course!). Thanks so much for your participation to the blogathon! 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Virginie,

Thank you for the comments and for allowing me to participate in the blogathon. I also still love her role in Casablanca, though it took me some time to put it in the context of her other films. I find it interesting that she wasn’t crazy about it herself even though it’s one of her most (if not the most, at least to a non-classic film fan public) well-known role of hers.

Tam

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful analysis. I like what you said about Hedda Gabbler’s complexity and dignity being ageless. She’s a fascinating character, as are the themes in this play.

Thanks for the links! 🙂

LikeLike

Hi silverscreenings,

Thank you for the comments (and for writing a very thoughtful blog post about the film yourself last year 🙂 ). I agree Hedda is a fascinating character, especially in the context of her time (though I do think she’s still fascinating in the context of our time).

Tam

LikeLike

It’s all a blur since I saw her films as a child (on one of those classics channels) but I’ve always loved Ingrid Bergman, so I enjoyed reading this.

LikeLike

Hi Joanne,

Thank you for your comments. I’m glad you enjoyed the post :-).

Tam

LikeLike

Very intriguing.

LikeLike

Thanks, Latifa!

Tam

LikeLike