Photo Credit: Book cover for the Dover Thrift Edition of Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, 2002, uploaded 6 July 2008 by Wolf Gang: Wolf Gang/Flickr/CC BY SA 2.0

“‘Once—twice—you gave me the chance to escape from my life, and I refused it: refused it because I was a coward.'” (Lily Bart to Lawrence Selden, The House of Mirth, Wharton, p. 162)

***Some spoilers***

I’ve talked about looking at different works of art (including fiction) the second time around and for me, rereading works I read many years ago has helped to shift my perspective of them. Recently, I took another look at Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar and I continue to reread works to see what effect they have on me now.

One book always on my “to reread” list is Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth. Wharton is one of my favorite authors, both because I love Victorian-era literature and because she is one of the godmothers of psychological fiction. Not only that, Wharton has a reputation for having been sympathetic to women’s plight and the limited lives women endured in the nineteenth century so in some ways, she was an early feminist writer as well.

All of this is true of The House of Mirth, although it took me several rereadings to realize this. The first time I read the book, I adored it. I loved the protagonist Lily Bart and saw her as a feminist character in the way she didn’t settle for just any man and in many ways defied the Victorian womanhood ideal of the separate spheres. I also loved the elegance of the world Wharton describes (and knew so well in real life) of the New York elite at the turn of the century. In fact, Wharton’s novel was one of the first pieces of classic literature I read after I rejected potboiler romances in my teen years and decided to move towards literary fiction and I credit the book for beginning my love affair with Victorian literature which still endures today.

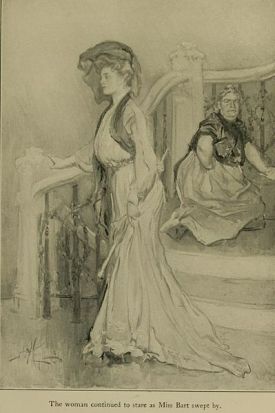

The second time I read this book was years later while in graduate school. While my passion for the book hadn’t cooled (I still find it one of the most page-turning books of the nineteenth century), my passion for Lily Bart was a different story. By that point, I had studied quite a lot of women’s fiction and women’s history. I recognized Lily Bart as not the feminist heroine I had envisioned her the first time. On the contrary, she was anything but. She was in fact rather vain and selfish, the Victorian version of the entitlement generation girl. I had little patience for the ease with which she criticized others and the snobbish airs she took on of the well-to-do New York society in which she circulated but, in terms of money, power, and position, did not belong. I was especially affected by the way she constantly put down the one real friend she has, Gerty Farish, whom she sees as shabby, poor, and sanctimonious because Gerty doesn’t live on Fifth Avenue, doesn’t attend afternoon teas, and works hard to help young women in worse conditions than herself.

Photo Credit: Illustration from The House of Mirth, 1905 by A. B. Wenzell. From a scene where Lily Bart is leaving Lawrence Selden’s apartment house and passes by a woman cleaning the stairs. Note Bart’s haughty pose, as if to say “How dare this lowlife get in my way of passing on the stairs?”: Sherurcij/Wikimedia Commons/PD 1923

My recent third rereading didn’t change my views much about what kind of character Lily Bart is. I still see her, for the most part, as self-centered and shallow, though not without other redeeming qualities (like her self-awareness). However, this time around, I understand why she has to be this way. I saw Lily Bart from the point of view of her creator rather than from a reader’s point of view. Yes, Bart has all these not-so-attractive characteristics but Wharton created her that way deliberately because she was anxious to show the waste “old moneyed” New York put upon young women in order to be accepted in that society. Bart is a product not just of her time but her social class. She is what young women who wanted to belong to the wealthy circle of New York society, especially if they were beautiful (and we have many hints that Bart is beautiful, both in her own eyes and the eyes of others) had no choice but to be. Beautiful young women in turn-of-the-century New York were taught their only asset is their looks and they had better make the most of them while they could and snag a rich husband, the richer the better (because the only power and respect a wealthy woman held depended on how big her husband’s bank account was). So Lily’s obsession with finding a rich husband may seem artificial by contemporary standards, to be sure, but she has been taught nothing else. So even as I wasn’t able to like her much, I could at least understand and sympathize with her.

The one character I found difficult to sympathize with in this rereading was Lawrence Selden. In my previous readings of the book, I hadn’t paid much attention to him beyond the way Bart and others saw him. But this time, I realized Wharton his role in the book is less as Bart’s love interest (of a sort) and more a view of the separate spheres from the male perspective. Selden is as egocentric as Bart is but he’s more hypocritical about it. He presents himself as a good Samaritan, someone with good intentions towards Bart, and as the story develops, it’s clear he wants to be her hero, her knight in shining armor. He wants to “save” her from the shallowness and callousness of the high society she wants to desperately to rein and free her from her attraction to this shallow and callous life. Because, like every Victorian beautiful woman, she is too dense to know what she’s getting herself into and needs a man to show her.

But in reality, Selden doesn’t love Bart as he claims. He loves her artificiality, her beauty, and her vivaciousness. In short, he wants a trophy wife. He seems unaware of his male privilege as he pelts her constantly with a “just do it” kind of attitude. He doesn’t seem to understand women of her position cannot easily shake off a prosperous marriage proposal like men can because their entire reputations and identities rely on marriage. In fact, Gerty Farish, who is his cousin, despite being removed from that level of society, seems to understand this more than he does. She explains to him,

“You know how dependent [Lily] has always been on ease and luxury—how she has hated what was shabby and ugly and uncomfortable. She can’t help it—she was brought up with those ideas, and has never been able to find her way out of them.” (Wharton, p. 142)

But Selden either can’t or won’t understand this and as a result, he constantly plays emotional games with Bart for not being able to shake herself away from that society. Even as she makes it clear how difficult it is for her, he assumes she will eventually leave the wealthy society behind to go off with him and when she doesn’t, he reacts in a childish way. For example, they make a date for him to come to Bart’s house to discuss the matter but Selden happens to see Bart going into the house of another man and without asking for explanations, takes off for Europe the next day without so much as a goodbye.

Finally, I realized the ending of the book is more ambiguous than I first realized. There’s been some dispute about Wharton’s intentions for the ending of The House of Mirth. In Charles McGrath’s article “Wharton Letter Reopens a Mystery”, he describes the final scene with Bart:

“[S]he packs away her few remaining gowns and carefully settles her accounts, writing a check that will clear her last remaining debt, and then deliberately takes a larger dose [of chloral hydrate, a sleeping potion] than usual.” (McGrath, par. 3)

The description sounds very much like a preparation for suicide (tying up loose ends, taking an overdose of a sleeping drug). But the book doesn’t make this so clear. Bart muses to herself:

“She knew she took a slight risk in [taking a larger dose of the drug]— she remembered the chemist’s warning. If sleep came at all, it might be a sleep without waking. But after all that was but one chance in a hundred: the action of the drug was incalculable, and the addition of a few drops to the regular dose would probably do no more than procure for her the rest she so desperately needed….” (Wharton, p. 170)

Thus, the ambiguity in the text lies between whether Bart meant to kill herself or whether it was an accident. McGrath presents both sides of the argument. On the one hand, “[s]ome critics have argued that the suggestion of mere risk-taking here, and not intentional overdosing, is simply a euphemism of the kind frequently employed in Lily’s world, where well-bred people never referred to suicide” (McGrath, par. 4). On the other, “[o]thers have argued that it is precisely the careless, accidental nature of Lily’s death that is so tragic, because carelessness, a failure to think things through, is her great flaw, while her great strength is an ability to bounce back” (McGrath, par. 7).

McGrath’s article is all about a letter written by Edith Wharton to a doctor asking for his advice. In the letter, she asks, “‘What soporific, or nerve-calming drug, would a nervous and worried young lady in the smart set be likely to take to, & what would be its effects if deliberately taken with the intent to kill herself? I mean, how would she feel and look toward the end?’” (McGrath, par. 10). Later, she admits she is asking for a character in a book she is writing. For Hermione Lee, a Wharton biographer, the letter proves Wharton’s initial intention to make Bart’s end a suicide but the decision may have been curtailed as Wharton progressed in writing the book:

“‘I think it’s quite likely that in December 1904, Wharton was thinking that Lily was going to commit suicide, and that by the time she came to the ending, months later, she changed her mind, because of the way those last pages hold onto so many moral positions at once. I think that, as she went on, she decided that it would be more effective if she left the ending ambiguous. It’s actually a much greater book if we don’t know for sure.’” (as quoted in McGrath, par. 19)

According to Lee, Wharton, with her propensity for psychological fiction, went with a more ambiguous ending rather than a clear-cut one.

I believe the ending of the book goes even further. The complexity of Bart’s character comes to a climax in this scene in that her death is both an accident and a suicide. I think Bart’s state of mind was such that she unconsciously had suicide on her mind but the act was more accidental, as she tries to convince herself that taking an overdose of the drug won’t really kill her.

This book is still on my permanent “to reread” list, as I find something new to explore in it every time I read it. I don’t think my changing perspectives, even the less positive ones about Selden’s character, take away from my enjoyment of the book. Evolving perspectives only make a book more interesting, if not always more likeable.

Works Cited

McGrath, Charles. “Wharton Letter Reopens a Mystery.” The New York Times. The New York Times Company, 2017. 21 November 2007. Web. 13 September 2017.

Wharton, Edith. The House of Mirth. Macmillan Collector’s Library, Pan Macmillan, 2017 (first published in 1905). Kindle digital file.

Very interesting how time can change your perspective and the way you viewed this book!

LikeLike

Hi Alyssa,

Thank you for your comment! I think we evolve as people over time so just as our reading tastes change, so do our perspectives on books we reread :-).

Tam

LikeLike

I’ve never read this, but it sounds interesting

LikeLike

Hi Katrina,

It’s a great book and actually I found it quite engaging. It is written in the Victorian style so it goes off sometimes on descriptive narrative that drags but when you get past those, it’s really interesting.

Tam

LikeLike